#premenstrual exarcerbation

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

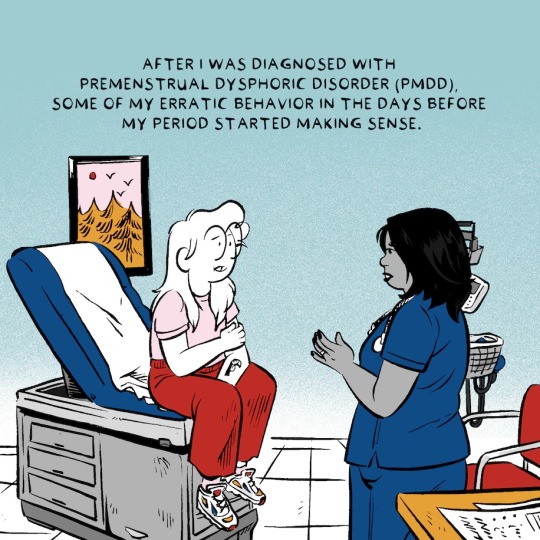

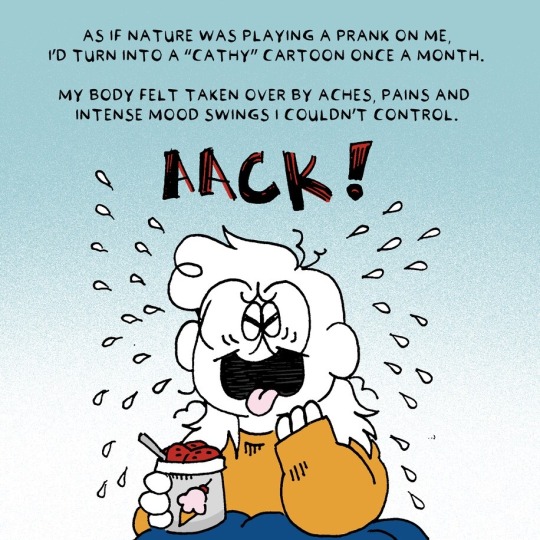

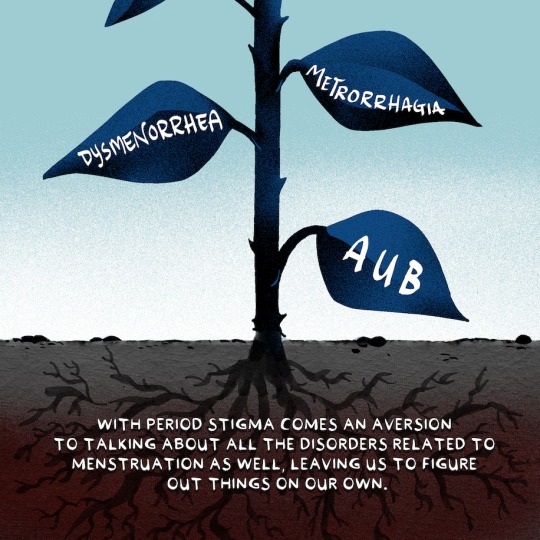

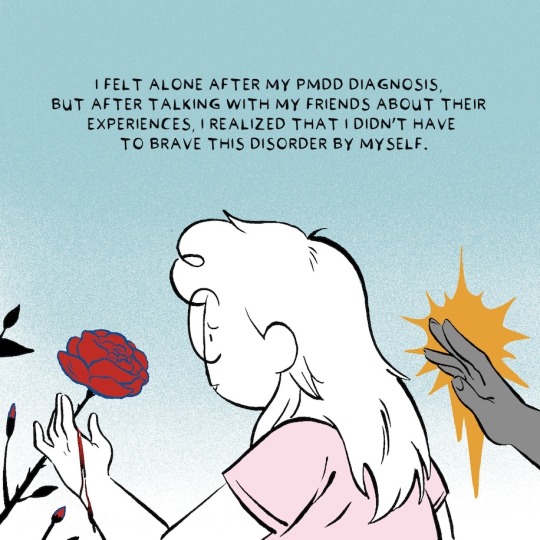

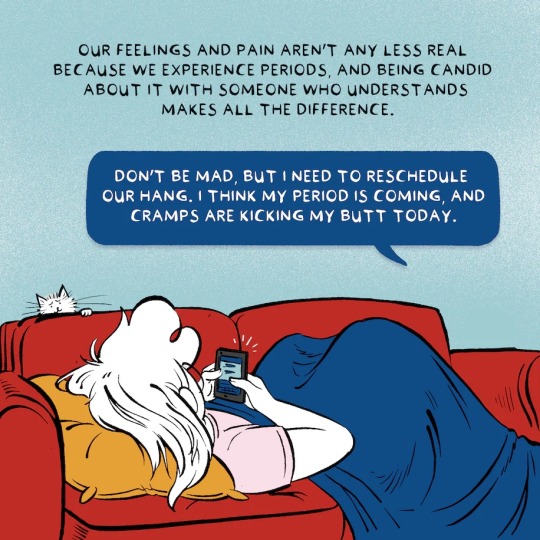

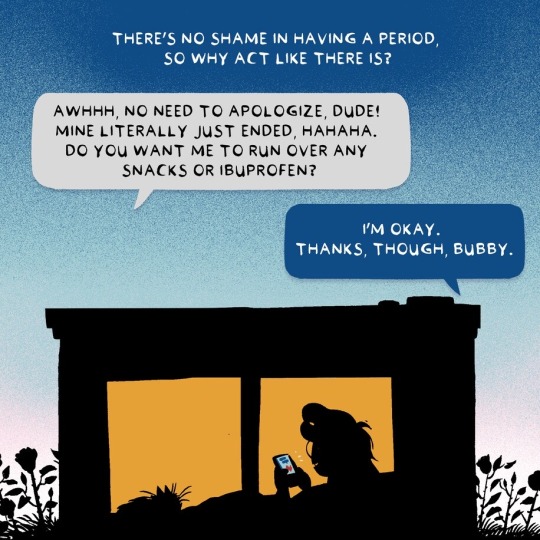

Comic from the Washington Post

#pmdd#premenstrual dysphoric disorder#pme#premenstrual exarcerbation#period#mental health awareness#living with pmdd#mental health#actually pmdd#pmdd awareness#pmddsupport#comic#Washington post

671 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me. My symptoms developed in my 30s and rapidly got worse over the course of months. My rage during the premenstrual phase was becoming more violent to the point that I was worried for the safety of those around me. In that worry I also started to wonder if my child would be better off without a monster for a parent. I later read that up to 30% of those with PMDD will attempt suicide and even though I didn't, I can very easily see how it happens.

My doctor believed me and we worked towards finding a way to manage it. I am infinitely better now. I use both birth control and an SNRI. My kid gets to have a decent and safe Mom.

I never, ever wanted to be on a medication that would effect my brain. But for my kid? I will take that pill with a smile every day until menopause saves me from this God forsaken disorder. But I do worry about the conservative justices of SCOTUS wanting to overturn Griswold and its potential to affect my family.

PSA about PMDD

I just had to post this. I had to get the word out about something that needs to be more widely known and understood.

First of all,

PMS is not a joke. It is horrible and shitty to have to go through.

Second of all,

PMDD is different and is also not a joke.

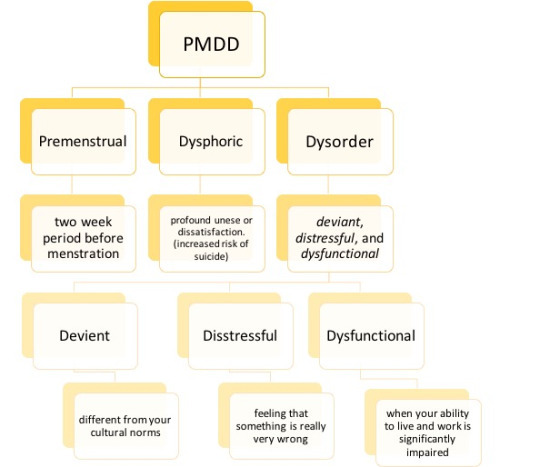

Now let me explain for those who don’t know. PMDD stands for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder. Let’s look at those words more closely.

Premenstrual: Roughly speaking the two-week period leading up to a woman’s menstruation every month.

Dysphoric: Dysphoria is described as being “a profound state of unease or dissatisfaction. In a psychiatric context, dysphoria may accompany depression, anxiety, or agitation.” And can often indicate an increased risk for suicide.

Disorder: many clinicians will describe psychiatric disorders as deviant, distressful, and dysfunctional patterns of thoughts, feelings and behaviors

NOW, lets break down disorder into those 3 parts

Deviant: thoughts or behaviors that are different from most of the rest of a given cultural context

Distress: a subjective feeling that something is really very wrong

Dysfunction: when a person’s ability to work, and live is clearly and often measurably impaired.

These 3 things are what the field of psychology would like to call the criteria for diagnosing someone with a mental or behavioral illness. That last one in particular. Now that was a lot of info so how about I make this all a little bit more visual…

So now that you understand what PMDD means and that it is a real diagnosable illness, lets take a look at what it means to live with it.

PMDD was added to the DSM in its most recent addition in 2013, the DSM5 lists the following 11 symptoms as characteristic of PMDD

· Marked lability (e.g., mood swings)

· Marked irritability or anger

· Markedly depressed mood

· Marked anxiety and tension

· Decreased interest in usual activities

· Difficulty in concentration

· Lethargy and marked lack of energy

· Marked change in appetite (e.g., overeating or specific food cravings)

· Hypersomnia or insomnia

· Feeling overwhelmed or out of control

· Physical symptoms (e.g., breast tenderness or swelling, joint or muscle pain, a sensation of ‘bloating’ and weight gain)

Speaking as someone who has been diagnosed with this by an actual doctor, I can say that PMDD is the hardest thing I have ever had to deal with, when I am not in the premenstrual period I am constantly thinking about how far away from it I am. I plan things around it because I can, because it comes every month like clockwork. All I can do is try and enjoy my self for the two weeks every month when I am not in absolute hell. And when it comes, everything is a struggle. I have to force myself to go to class, force myself to talk to people, force myself to shower, brush my teeth and do anything other than pull myself out of crying fits and into numbness, out of anxiety attacks and into the temptation to self harm.

After it is all over I try and move on and recover and live my life to the fullest until it comes back but that is all I can hope for. A half life.

So let me reiterate, PMDD is not a joke. If those symptoms or my testament hit a little too close to home, please share your concerns with a doctor and get a formal diagnosis and treatment. And for everyone else, all I ask is that you spread awareness and try to think twice the next time you think about accusing a girl of PMSing because ever since 2013 this has been a bona fide mental illness. We as a society can not claim that we are working towards reducing the stigma on mental illnesses if we are only doing so for a select few on a list of many.

Please reblog and spread awareness.

#pmdd#premenstrual exarcerbation#premenstrual disorder#premenstrual dysphoric disorder#living with pmdd#pmdd awareness#chronic illness#snri#birth control#supreme court#griswold v. connecticut#clarence thomas

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

Let's Talk PMD Awareness

Saturday, March 18 at 11am ET / 3pm UK

- - -

What's happening during PMD Awareness Month? How can I get involved? How can I speak more openly about my lived experience?

If you're eager to get involved with PMD Awareness Month this year (it's next month!), join us this Saturday for Let's Talk PMD Awareness, a relaxed webinar and panel discussion all about PMD awareness. Bring your questions and your notebook to plan how you will Spark Change.

Find out what is going on for PMD Awareness Month (April) and join a panel of folks as we chat about:

What does PMD Awareness mean to you?

Why does PMD Awareness Matter?

What worries you about opening up about PMDD/PME?

What will you be doing for PMD Awareness Month?

Why is it important to involve men in the PMD conversation?

What have been some outcomes of you speaking about PMD?

and more!

Closed captions will be used for accessibility.

(Info pulled from IAPMD’s newsletter and the EventBrite post for the meeting)

#pmdd#pmd#pme#afab health#invisible disability#premenstrual dysphoric disorder#premenstrual exarcerbation#advocacy#disability advocacy

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

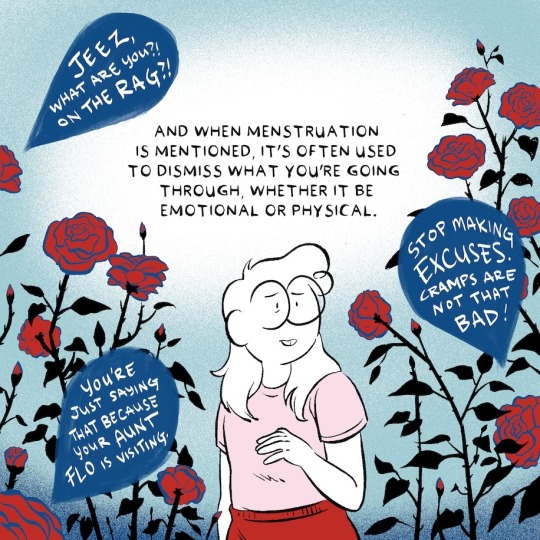

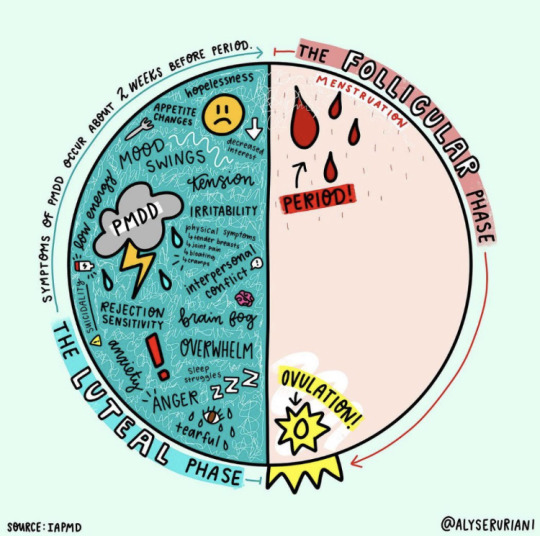

Art by @alyseruriani for PMD awareness month 2022

#pmdawarenessmonth2022#art#illustration#pmdd#pme#pmd#premenstrual exarcerbation#premenstrual disorder#premenstrual dysphoric disorder#living with pmdd#mental health#actually pmdd#mental health awareness#pmdd awareness#pmddsupport#afab problems#afab health#women’s health#pms

437 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey all!

Below is a link for a petition to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services requesting they fund research into a cure for PMDD. ✍🏼 Only takes a second and you can find more information in the petition itself.

https://chng.it/ThPDwXJpM6

Thank you @purplekittenwar for making me aware of this!

#pmdawarenessmonth2022#pmdd#pme#womens health#afab health#premenstrual dysphoric disorder#premenstrual exarcerbation#living with pmdd#mental health#actually pmdd#mental health awareness#pmdd awareness#pmddsupport#petition

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

How am I supposed to operate under these circumstances? [chronic illness]

#pmdd#premenstrual dysphoric disorder#chronic illness#mental health#mental health awareness#premenstrual exarcerbation#pme#pmd#living with pmdd#actually pmdd#pmddsupport

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sign up at IAPMD to join a group!

There’s no commitment to attend regularly. You can switch between groups as works for you (or attend multiple sessions).

I’ve attended several meetings and found a lot of support in and empathy from other folks also going through PMDD/PME.

#afab health#pmdd#pme#pms#premenstrual disorder#premenstrual dysphoric disorder#premenstrual exarcerbation#afab problems#womens health#chronic illness#living with pmdd#mental health#actually pmdd#mental health awareness#pmdd awareness#pmddsupport

12 notes

·

View notes

Link

As a lover of history and someone who suffers from PMDD, I find this fascinating.

As a teenager, Sylvia Plath vividly understood the extent to which her body steered her. “If I didn’t have sex organs, I wouldn’t waver on the brink of nervous emotion and tears all the time,” she wrote in her journal in 1950. Ten days before her death, she had come to believe that “fixed stars/Govern a life.” It turns out that Plath was probably right – more right than she could have possibly known – about her biology and her fate. But when Plath’s journals were first published in 1982, what was most obvious about her was the supercharged nature of her emotions. Whatever causal agents may have been governing Plath’s life, they were blown back by the force of her personality.

As unmistakable as were Plath’s volatile emotions in the 1982 journals, the heavy editing of the text necessarily made it hard to discern the patterns to her moods. Even so, there did seem to be a detectable pattern, and it did not seem then, nor had it seemed to the people closest to her during the last years of her life, to be merely a function of temperament. In the weeks before her suicide, Plath’s physician, John Horder, noted that Plath was not simply deeply depressed, but that her condition extended beyond the boundaries of a psychological explanation.

In a letter years later to Plath biographer Linda Wagner-Martin, Horder stated: “I believe … she was liable to large swings of mood, but so excessive that a doctor inevitably thinks in terms of brain chemistry. This does not reduce the concurrent importance of marriage break-up or of exhaustion after a period of unusual artistic activity or from recent infectious illness or from the difficulties of being a responsible, practical mother. The full explanation has to take all these factors into account and more. But the irrational compulsion to end it makes me think that the body was governing the mind.”

For at least the past 10 years it has been generally assumed that Plath fit the schema of manic-depressive illness, with alternating periods of depression and more productive and elated episodes.

The hypothesis that Plath suffered from a bipolar disorder is persuasive. But in late 1990, another, even more intriguing medical theory emerged. Using the evidence of Plath’s letters, poems, biographies and the 1982 journals, a graduate student named Catherine Thompson proposed that Plath had suffered from a severe case of premenstrual syndrome. In “Dawn Poems in Blood: Sylvia Plath and PMS,” which appeared in the literary magazine Triquarterly, Thompson theorized that Plath’s mood volatility, depressions, many chronic ailments and ultimately her suicide were traceable to the poet’s menstrual cycles and the hormonal disruptions caused by PMS.

Thompson pointed out that Plath unwittingly recorded experiencing on a cyclical basis all of the major symptoms of PMS, as well as many others, including low impulse control, extreme anger, unexplained crying and hypersensitivity. She also suffered many of the physical symptoms associated with PMS, notably extreme fatigue, insomnia and hypersomnia, extreme changes in appetite, itchiness, conjunctivitis, ringing in the ears, feelings of suffocation, headaches, heart palpitations and the exacerbation of chronic conditions such as her famous sinus infections.

Thompson compared Plath’s reported mood and health changes with the journals, letters and biographies and found that her symptoms seemed to appear and disappear abruptly on a fairly regular schedule, with clusters of physical symptoms and depressive affect followed by dramatic changes in outlook and overall physical health. Those patterns can be directly linked to the dates of Plath’s actual menses, particularly in 1958 and 1959, when she most habitually noted her cycles. Judging from the pattern of Plath’s depression and health in late 1952 and in 1953 until her Aug. 24 suicide attempt, Thompson posited that “it seems reasonable to conclude that this suicide attempt was directly precipitated by hormonal disruption during the late luteal phase of her menstrual cycle and secondarily by her loss of self-esteem at being unable to control her depression.”

Thompson showed that a well-known journal entry from Feb. 20, 1956, is clearly traceable to Plath’s menses, to which she refers directly a few days later. The journal fragment takes on new meaning in light of having been written during the physically and emotionally debilitating luteal phase of Plath’s cycle: “Dear Doctor: I am feeling very sick. I have a heart in my stomach which throbs and mocks. Suddenly the simple rituals of the day balk like a stubborn horse. It gets impossible to look people in the eye: corruption may break out again? Who knows. Small talk becomes desperate. Hostility grows, too. That dangerous, deadly venom which comes from a sick heart. Sick mind, too.” On Feb. 24, the same day she notes in her journal that she has a sinus cold and “atop of this, through the hellish sleepless night of feverish sniffling and tossing, the macabre cramps of my period (curse, yes) and the wet, messy spurt of blood,” Plath wrote a letter to her mother blaming her dark mood on her physical health: “I am so sick of having a cold every month; like this time, it generally combines with my period.”

By the fall of 1962, the poems (which Plath carefully dated as they were completed) seem to follow a pattern of metaphorical renewals and optimistic transformations for roughly two to three weeks of artistic production, then jagged, seething accusations and aggression for a couple of weeks.

Thompson’s PMS theory has been largely ignored by Plath scholars. But it immediately gained two important supporters: Anne Stevenson, Plath’s controversial biographer, and Olwyn Hughes, Plath’s former sister-in-law, whose letters were published in a subsequent issue of Triquarterly. Though oddly defensive in tone, Stevenson’s letter does commend Thompson for her “invaluable contribution to Plath scholarship … Certainly no future study of Plath will be able to ignore the probable effects of premenstrual syndrome on her imagination and behavior.” And it states that she wishes she had been able to utilize Thompson’s insights in the writing of her own work on Plath.

A letter from Olwyn Hughes also congratulates Thompson for her scholarship, but unlike Stevenson, Hughes practically stumbles over herself in amazement at the PMS theory. Hughes, who was quoted in Janet Malcolm’s book “The Silent Woman: Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes” as characterizing her long-dead sister-in-law as “pretty straight poison,” wrote to Thompson: “It is quite a shock to digest all this – after thinking for so long that Sylvia’s subconscious mind was her prison, and to suddenly realise it may well have been in part, or wholly, her body. But it certainly tallies with Ted’s mentions – he has always felt some chemical imbalance was involved.”

Hughes further points out that Ted Hughes had spoken of Plath’s ravenous appetite just prior to her periods and asks, “I wonder if that is a known characteristic of PMS?” (According to the PMS literature, it is.) But most tellingly, Olwyn Hughes explains that “one of the reasons I was so bowled over by your piece is that Sylvia’s daughter, very like her physically, suffers quite badly from PMS but is, in these enlightened times, aware of it and treats it.”

Dr. Glenn Bair, one of the leading experts on PMS treatment and research in the United States, confirmed to Salon that PMS is typically passed from mother to daughter. In a rare interview about her parents, Frieda Hughes told the Manchester Guardian in 1997 that after the “collapse of her health,” including extreme fatigue and gynecological problems, she underwent a hysterectomy in her 30s.

After a careful review of Thompson’s article, of a seven-page monthly breakdown of Plath’s symptoms for 1958 through 1959 and of the documented evidence of Plath’s pregnancies and postpartum symptoms of 1959 through 1962, Bair said, “If you hack through the PMDD criteria, I think that you’ll find that she fits the PMDD profile.”

#history#pmdd#pme#PMD#premenstrual dysphoric disorder#premenstrual exarcerbation#living with pmdd#actually pmdd#pmdd awareness

170 notes

·

View notes